I love discovering new things about the place I live.

My husband and I like to walk out of the house without a goal in mind and wander like tourists, finding new things along the way. We call it flaneuring, a verb some friends with a similar passion contrived from the French word with no English equivalent.

The following elaboration is stolen directly from Wikipedia:

[The term flâneur comes from the French masculine noun flâneur—which has the basic meanings of “stroller”, “lounger”, “saunterer”, “loafer”—which itself comes from the French verb flâner, which means “to stroll”. Charles Baudelaire developed a derived meaning of flâneur—that of “a person who walks the city in order to experience it”.]

Occasionally I get the same sort of sensation when flipping casually through books, especially if the book has attractive photos.

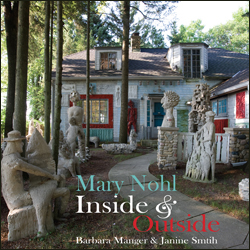

Book cover, published by UW Press

When I first picked up Barbara Manger and Janine Smith’s book, “Mary Nohl Inside & Outside,” I felt I’d wandered into a new-to-me neighborhood along Lake Michigan and was peeping into the yard of someone very intriguing.

Mary Nohl, an artist who landscaped her large lakefront property and decorated her house with her own sculptures, paintings, carvings, and designs, is not a complete unknown. The Kohler Foundation owns the estate, which is also listed on the National Register for Historic Places, and Ms. Nohl was posthumously awarded the Wisconsin Visual Art Lifetime Achievement Award in 2008.

But, to trip unexpectedly into her world through the pages of the book was for me to see a new side of Wisconsin. The book authors write that Ms. Nohl hated being labeled, so I’ll try to avoid it, but she is one of the many less-than-world-known artists who have graced the Wisconsin landscape with magical fantasy worlds of their own creation. The more I stroll beyond the main route, drive off the thoroughfare, the more of these people I “meet.”

For those of us in Madison next week, Barbara Manger and Janine Smith, artist and bookmaker respectively, will be presenting at the Wisconsin Book Festival on Wednesday, October 7 from 5:30 – 7 PM at the Chazen Museum of Art. They will be sharing more insight, I’m sure, into the character of Ms. Nohl and her eclectic body of work.

If you are out flaneuring, maybe you will wander in. Or find something else of interest. You never know!

by Jessica Becker, Director of Public Programs, Wisconsin Humanities Council

Posted by Jessica Becker

Posted by Jessica Becker